The Burruss Years (1919-1945)

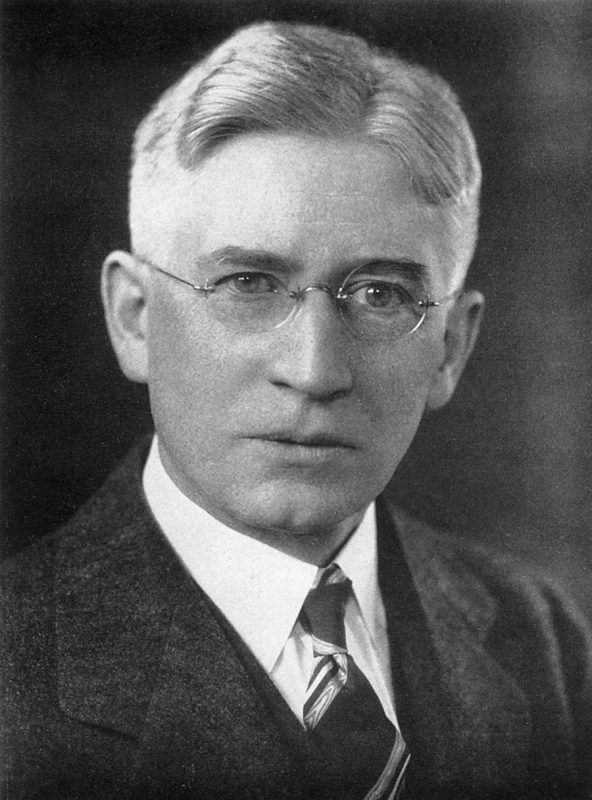

The board of visitors, meeting in Richmond on June 12, 1919, elected Julian Ashby Burruss as Virginia Tech’s eighth president. Burruss was the first Tech alumnus tapped for the position.

An 1898 VPI graduate with a B.S. in civil engineering, Burruss was working on his Ph.D. degree at the University of Chicago (he received the degree in 1921) and serving as the first president of the Normal and Industrial School for Women (now James Madison University). Since he had already accepted a summer instructorship at the University of Chicago, he requested that the board postpone the date he would commence his presidency until Sept. 1, 1919. Consequently, the board appointed its rector, J. Thompson Brown, to serve as acting president until Burruss could finish his commitment. When Burruss did report for work, he was the first VPI president with experience and professional study in school administration, curriculum, and school finance.

Shortly after beginning his duties, Burruss developed a list of six ultimate goals, which would serve as guideposts during his 26 years as president. Those goals were “[t]o do what Virginia needs to have done by this particular institution; to maintain highest standards in all endeavors; to provide a staff organization adequate to carry on the work efficiently; to provide a physical plant adequate for the work to be done; to so conduct the institution as to secure desired efficiency with the greatest economy; and to provide funds necessary for doing the job that is to be done.”

Burruss began his administration with a physical plant inadequate for the influx of students returning from World War I service and in an atmosphere of unrest. He focused on three immediate and imperative reforms needed at the college: a revision of programs of instruction and of administrative structure, a better organization for student life, and an increase in physical accommodations.

Almost immediately, he succeeded in getting a larger appropriation from the state and in establishing new guidelines for the agriculture and engineering curricula. One of the first problems he tackled was the administrative organization. The college’s dispersion of authority was too wide, confusion existed about where responsibility would be placed, and the spending of funds lacked coordination. Burruss abolished four deanships: general faculty, graduate department, academic department, and applied science department. He broadened the scope and authority of the deans of agriculture and engineering and established the post of dean of the college (general departments). He abolished the office of the college surgeon and hired a full-time health officer. He revised the corps’ constitution and the “rat regulations.” He also created a business manager office for the college. He placed the Agricultural Experiment Station and Extension Service directors under the dean of agriculture. He abolished the registrar’s office and placed the duties under the dean of the college. He brought athletic activities directly under the control of college authorities instead of letting them remain under the joint management of students and faculty. His reorganization improved the business management of the college, resulting in financial savings that were used to pay off old debts and to make repairs and improvements.

Most of the major changes instituted by Burruss occurred during his first eight years of office. In addition to the administrative changes discussed above, he instituted or oversaw a number of other changes. An Engineering Experiment Station was established in 1921, followed by an Engineering Extension Division in the session of 1923-24. Summer school was strengthened and organized on a quarter basis. Student orientation and guidance were initiated, and loan funds and scholarships were increased considerably. A chapter of Phi Kappa Phi was organized. Academic standards were raised to bring the college in line with the standards of nationally recognized colleges. Entrance requirements were increased to 15 units (later 16 units); a new grading system was established; and systems of honors, credit-hours, and quality credit were set up (1920). Burruss also developed a long-range plan for the physical development of the campus. In 1923-24 the college was fully accredited by the Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools of the Southern States, the first time it had been accredited.

Under Burruss’s guidance, the college grew significantly. During his 26 years as president, resident faculty members doubled in number; student enrollment increased from 477 in 1918-19 to 1,224 in 1926-27; the number of degrees awarded at commencement rose from 42 in 1919 to 163 in 1927; instructional departments increased from 23 to 31; the number of courses rose from 238 to 376; the staff of the Agricultural Experiment Station increased from 29 to 42, and its work was extended, particularly in agricultural economics, agricultural engineering, home economics, and rural sociology; the Agricultural Extension Service staff grew from 154 to 183; salaries and wages grew at an average of 60 percent and were doubled in some cases; and the annual budget for the college was more than doubled.

Although Burruss made many lasting changes, his most significant innovation was to persuade the board of visitors in 1921 to admit women as regular students. Twelve white women—it would be another 45 years before black women could enroll—registered that fall—five full-time and seven part-time—and all courses except the military were opened to them. But most student organizations would not admit them; the yearbook, The Bugle, derided them and refused to include them in the pages of students for nearly 20 years; and the corps of cadets opposed their presence on campus, sometimes making life unpleasant for the women.

The women produced their own yearbook, The Tin Horn, in 1925, 1929, 1930, and 1931; started their own basketball team, which they initially called the Sextettes and then, sometime before 1929, the Turkey Hens; formed their own clubs and social organizations, including, by 1929, a Women’s Student Organization; and introduced in 1934 their own women’s government entity, the Women’s Student Union. In 1939 The Bugle allotted two pages for the Women’s Student Union, the first token representation of women in the college yearbook. The following year, it included a section of women seniors and women senior officers, and in 1941, for the first time, it accorded the women full status as Virginia Tech students by interspersing their photos with those of male students in the civilian class section.

One of the original five full-time students, Mary Brumfield, transferred to the college from another school and, in 1923, became the first woman to graduate from Virginia Tech, earning a degree in applied biology. Three of the four remaining female students who enrolled with her graduated in 1925: Ruth Louise Terrett in civil engineering, Lucy Lee Lancaster in applied biology, and Carrie T. Sibold in applied biology. Billie Kent Kabrich, who majored in applied chemistry, left school before finishing, but transfer student Louise Jacobs filled her spot and graduated in 1925. Shortly after the women enrolled as undergraduate students, the first women enrolled in graduate programs. Beginning in 1923 women, including Brumfield, comprised about 2 percent of the graduate students. One of the early graduates was Ella Russell, who received her undergraduate and master’s degrees from VPI in 1926 and 1928, respectively. She joined the chemistry department, probably becoming the first alumna on the faculty, and taught until her death in 1949.

Another far-reaching move of Burruss, this time in 1923, was to modify the mandatory four-year military requirement for male students to two years and to make the last two years optional. This action set the stage for a larger civilian student body. The corps, which had embarrassed the college on numerous occasions with its antics, became more disciplined—at least for two years. The 1925 Sophomore Night left, among other surprises, farm animals and a beehive in the barracks, and wagons and farm equipment on a barracks roof. After the sophomore class received the bill for the cleanup and other charges related to the incident, the destructive aspects of Sophomore Night were dropped, and the corps began channeling its energy into more productive activities.

On May 28-30, 1922, the college held its Golden Jubilee, a celebration commemorating its 50 years of existence. To accommodate an expected crowd, the college erected a huge circus tent capable of seating more than 3,000 people. Pup tents were also erected to house students giving up their rooms to returning alumni. The celebration sported exhibits; open houses; College Day ceremonies that included a welcome by Gov. E. Lee Trinkle and speeches by University of Virginia President E. A. Alderman, Washington and Lee University President Henry Louis Smith, Ohio State University President William Oxley Thompson, Southern Ruralist Editor C. A. Cobb, and Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company President Homer L. Ferguson; and Alumni Day ceremonies that included a cadet parade, accounts by one or more representatives for every year of the college’s existence, recognition of the entire class of 1875 in attendance, a luncheon prepared by J. J. “Pop” Owens, and a jazz concert. Lawrence Priddy, president of the Alumni Association, proposed that alumni raise $50,000 toward building a war memorial hall that would include a gymnasium and quarters for visiting alumni. He secured pledges of $72,742 within 17 minutes. U.S. Senator Claude Swanson, class of 1877, and Gulf Smokeless Coal Company President Major W. P. Tams, class of 1902, delivered speeches for Alumni Day. The final activity was commencement, with William E. Dodd, class of 1895 and distinguished professor of American history at the University of Chicago, delivering the commencement address.

Physical improvements during the first eight years of the Burruss administration included repairing all existing buildings; remodeling many buildings; erecting campus lights; purchasing 255 acres of land and leasing 227 additional acres; paving roads through the campus; starting a landscape program; replacing the old decentralized heating distribution system with a centralized system; rebuilding and extending the electric distribution system; building a new sewage disposal plant jointly with the Town of Blacksburg; completing the McBryde Building of Mechanic Arts; constructing a new engine room for the power plant; installing fire escapes on all buildings; and erecting several farm buildings, professors’ homes and cottages, a greenhouse, beef and sheep barns, a poultry service building, one floor of Patton Hall, the Agricultural Extension Building (now Sandy Hall), War Memorial Gymnasium, part of Davidson Hall, Barracks No. 6 (now Major Williams Hall), Miles Stadium, and an Extension Division Apartment House.

During the remainder of the Burruss administration, the following buildings were added to the campus: Eggleston, Campbell, Hillcrest, Hutcheson, one unit of Smyth, Saunders, Seitz, Agnew, the remaining three floors of Patton, Davidson (completed), Holden, Squires Student Center, Burruss (called the Teaching and Administration Building initially), a Henderson Hall addition, Owens, Mechanical Engineering Lab, new Power House, Faculty Center (later became part of Donaldson Brown and now used as part of the Graduate Life Center), and the University Club. An airport, hangar, and shop were also built.

The college coal mine was closed in 1923 since it cost more to operate than was being saved.

Another event of note on campus in the 1920s was the founding of the Future Farmers of Virginia, which later grew into a national organization, the Future Farmers of America. Walter S. Newman, a 1919 alumnus who later became Virginia Tech’s 12th president, and professors H. C. Groseclose, a 1923 alumnus; E. C. Magill; and H. W. Sanders, a 1916 alumnus, all of the agricultural education department, founded the state organization.

By the end of his first 10 years, Burruss wanted to expand the concept of the school—his “visions and plan for a greater VPI,” he told the board of visitors—by offering new courses and attracting outstanding faculty.

The college began offering the first two years of its principal engineering curricula at four extension schools in the 1930s. The first was established in cooperation with the Virginia Mechanics Institute (later Richmond Professional Institute, now Virginia Commonwealth University) in 1930; that program was discontinued in 1970. Later, similar arrangements were made with the Norfolk division of the College of William and Mary (1931, discontinued in 1964); Bluefield College (1932, discontinued in 1964); and Lynchburg College (1932, discontinued in 1938).

The Virginia General Assembly cut the college’s appropriations by 7.5 percent and salaries by 10 percent in 1932 because of the depression. The depression-born Public Works Administration helped offset the loss of funds, however, by awarding a $1,066,000 loan to the college to construct several campus buildings. This loan, approved in January 1934, was later increased several times. In a cost-cutting move, Burruss suspended the home economics department for three years, the only program that was cut.

The college held its first Virginia Tech Day (also called High School Day) on May 2, 1936, with the Alumni Association bringing hundreds of high school students to visit the campus for a program of varied activities. The observance was not held in 1942 because of war conditions.

The practice of having a salutatorian and valedictorian for the senior class was discontinued after the 1936 commencement. The honors had been awarded on the basis of popularity from 1916 into the 1930s. In 1932, for example, Carol M. Newman, head of the Department of English and Foreign Languages and for whom Newman Library is named, wrote to President Burruss to apprise him of the senior class’s election of its valedictorian and salutatorian. The class had elected the third- and fourth-ranked students, both males. The top student was Miss F. R. Aldrich, with the second spot held by transfer student H. H. Addlestone. Aldrich’s quality credit average was 2.84 (with 3.0 being the highest possible average), and the elected valedictorian’s was 2.62. Newman defended the selection: “It is easy to see why the class made the selection it did, Miss Aldrich being a girl and Mr. Addlestone having been a student here for only two years.” The elected valedictorian, however, stipulated that an announcement be made that Miss Aldrich held the top academic honors.

In July 1936, college administration offices were moved from the old Administration Building to the newly constructed Teaching and Administration Building (now called Burruss Hall). Commencement exercises that same year were held in the T & A Building’s 3,000-seat auditorium.

The Alumni Association established an Alumni Loyalty Fund (later Alumni Fund) on June 5, 1937, “to promote the progress and growth of cultural and educational advantages” at the college. The first campaign ended on Dec. 31, 1939.

By the end of 1940 Burruss’s skill in obtaining and using funds from federal and state agencies established to address depression-era problems had resulted in vast improvements and new buildings on campus. Initially the new buildings were named according to their usage, but later, buildings were named for faculty members or alumni who had made significant contributions to the college.

Among the seven major new buildings completed in 1940, Seitz Hall was designed by the agricultural engineering staff, who also trained the construction crew and supervised much of their work. Another of the buildings, Hillcrest, was the first residence hall constructed specifically to house the college’s women students. Male students immediately dubbed it the “Skirt Barn.”

In 1942, when the corps of cadets requested a popular song for that year’s ring dance, Fred Waring and Charles Gaynor wrote “Moonlight and VPI.”

The war in Europe had an impact on campus as early as Oct. 16, 1940, when 509 VPI students were registered for the draft in Squires Hall under the Selective Service Act. Only juniors and seniors who had enrolled in ROTC were exempt from registering. When the United States entered World War II, the college accelerated its program, conducting a full quarter’s work in the summers, to enable students to graduate in three years. The accelerated program was discontinued in June 1946. For the first time in its history, the college conferred degrees at the end of winter quarter during the 1941-42 session. That historic commencement featured yet another historic event: Nathan Sugarman of Atlanta, Ga., received the first doctor of philosophy degree ever awarded by the school. Sugarman earned his degree in chemistry.

The many abnormal factors generated by the war helped create a major controversial situation for the Burruss administration and bought it to a head in the summer of 1942. The Hercules Powder/Radford Ordnance Works had lured away a large number of long-time, trained mess-hall employees with higher pay. Consequently, untrained and often inefficient and careless youngsters in their teens were, of necessity, hired as replacements—some 250 replacements for a force of 35 in the year July 1, 1941, to June 30, 1942—on campus.

The big labor turnover led to unsanitary conditions in the mess hall. Student complaints mushroomed in the summer of 1942, spurring the corps to march on July 27, 1942, to Burruss’s home to read a proclamation of protest against the aging president, who had increasingly insulated himself from the students. The ensuing unfavorable publicity—including reports in newspapers that the corps in one of the country’s largest military schools had rebelled—and his own personal interest led Gov. Colgate W. Darden Jr. to make several trips to the campus to interview student leaders and college officials. On Aug. 11 the board held a special meeting, attended by Darden, to consider the situation. The governor chided the board that it had allowed Burruss to carry such a heavy load and suggested that two people be hired to provide help for the overworked president. The board then determined that a reorganization of the college administrative work was needed to relieve Burruss, but it left the actual reorganization to Burruss. Additionally, the board named a special student life committee to meet with the president at least once a month to consider “all matters that affect student life,” a special committee of faculty and students “with power to act” on the mess hall situation, and a senior-privileges committee to study the matter of senior privileges, which had been eliminated following the demonstration. The campus slowly returned to relative normalcy, although the students surprised the faculty by petitioning for a course on race relations, which was approved and offered at the beginning of winter quarter 1943.

On Feb. 27, 1943, most of the seniors and juniors left for military duty, decimating the junior and senior classes. The college learned the same month that it had been selected for the Army Specialized Training Program and would be used to train Army engineers. Later, additional war training programs—a small naval pre-flight unit and a Specialized Training and Reassignment unit—were added. At the peak of the programs, more than 2,000 servicemen studied on the campus at the same time.

On March 10, 1943, the college honored Paul Derring for his 25 years of service to VPI. Derring, for whom today’s Derring Hall is named, had served as general secretary for the YMCA and had unofficially assumed part of the duties of the dean of students. Under his leadership, the YMCA played an important function for students, becoming by the mid-1920s the center of student life and activities.

The war continued to affect the college. VPI discontinued football during 1943 and 1944. Three former students received the Medal of Honor. Although it was kept quiet during the war, faculty and alumni cooperated in research that led to the development of the atomic bomb.

Through the efforts of Gov. Darden, who was possibly reacting to the efforts of nearly two decades to restrict and reduce the number of state-supported colleges and universities, the college merged on March 16, 1944, with nearby Radford State Teachers’ College, and most women’s programs were moved to Radford for the next 20 years. The state legislature officially changed the name of the Blacksburg school to Virginia Polytechnic Institute, and the Radford school became Radford College, Women’s Division of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute. Surprisingly, the president responsible for opening VPI to women paid little attention to the merger. The new affiliation between the colleges called for a board of visitors composed of 10 men, four women, and two ex-officio members. The president of VPI became the chancellor and chief administrator of Radford College, although Radford still retained its own president, David Wilbur Peters.

During negotiations for the merger, it became apparent that the attitude of the corps of cadets toward women on campus had changed considerably from that of the 1920s. John B. Spiers of Radford, representative of Montgomery County and Radford in the House of Delegates, was asked to prepare the bill merging the schools. According to the bill, all undergraduate women would be denied permission to reside on the Blacksburg campus. Upset over this provision, the corps of cadets passed a resolution urging the retention of female students at Blacksburg and even raised money to send a coed committee to Richmond to oppose this feature of the merger. A mimeographed statement showing the purported effects of the bill upon women’s education was prepared and distributed statewide. Women’s organizations throughout the commonwealth denounced features of the bill they thought discriminated against women.

A compromise was reached, allowing women under certain conditions to study on the Blacksburg campus. Women at VPI were required to study agriculture, engineering, applied science, or business administration. Those wanting to pursue teacher education studied at Radford. Home economics majors were split between the two campuses, with the first two years at Radford and the last two at VPI. Transfers between the two campuses could be accomplished without loss of credits. Women who wanted to continue with an advanced degree program studied on the Blacksburg campus. The fall of 1944 saw 10 Radford women taking the bus to attend aeronautical engineering classes at Virginia Tech, while eight student nurses took courses in sociology, psychology, and chemistry.

During the same year as the merger, the Teaching and Administration Building was renamed Burruss Hall by the board of visitors to recognize the president’s 25 years of service to the college. Burruss’s 26 years in office has remained a record for the number of years any president has served Virginia Tech.

It became obvious in the 1940s that the ever-mounting pressures of the presidency and advancing age were beginning to take their toll on Burruss and were affecting his performance of duties. At a special meeting in Roanoke on Jan. 4, 1945, the board of visitors granted Burruss a six-month leave of absence and named John Redd Hutcheson, director of the Agricultural Extension Service, as executive assistant to the president. Six days later, Burruss suffered a fractured vertebra in an automobile accident near Elliston. On Jan. 12, Col. James Woods, rector of the board, requested Hutcheson to “assume immediately all duties and activities of the president of the institution” until conditions warranted otherwise.

When it became clear that Burruss could not resume his duties, the board elected him president emeritus and named Hutcheson Virginia Tech’s ninth president. The day the board made its decision—Aug. 14, 1945—Japan surrendered, ending World War II and spurring a two-day celebration on campus.